Sayer Family Tree

Most of the information on this page is made possible by the work of JP Sayer and I am indebted to him and his daughter Mrs Gill Ward. JP Sayer met my grandfather, William Sayer, when he visited the UK in 1972, where they exchanged a number of stories.

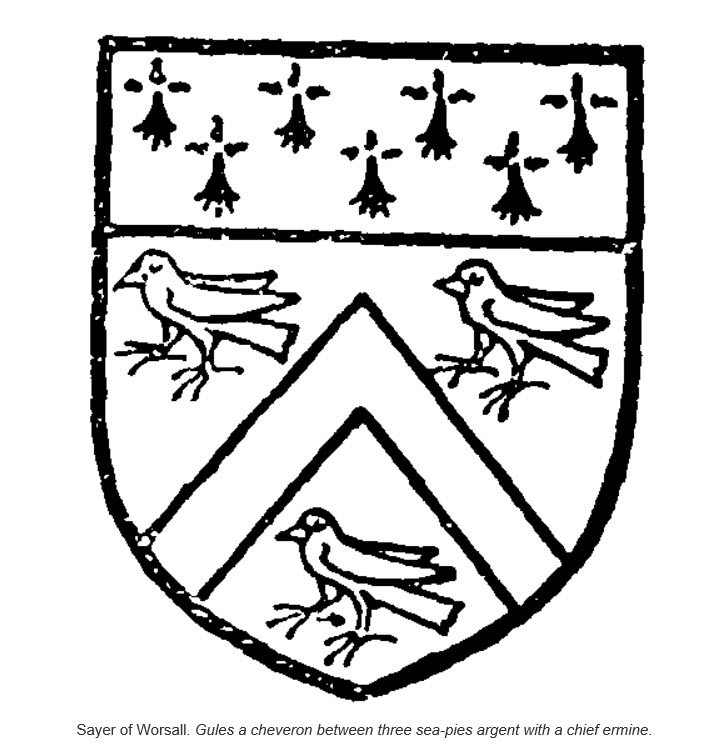

The Sayer Family of Worsall

The Manor of Worsall

On the south, or Yorkshire, bank of the river Tees and about five miles upstream from Yarm lay the manor of High Worsall. It was about 480 acres in extent and was granted by William I to the Bishopric of Durham in 1086, the first tenant being William de Vesci. It passed to the Hansards in the next century and to the de Setons in 1353.

In 1380 Agnes de Seton married John Sayer of County Durham, with the result that in 1401 the Sayers inherited half of the manor of Worsall and by 1468 were holding the entire property. It remained in their hands for the next two hundred years.

William Sayer and his Son John

In 1520 at the age of seventeen, William Sayer of Worsall, sixth in descent from the first John Sayer, married Margaret, the daughter of Sir Thomas Fairfax of Walton. She was a granddaughter of Lady Margaret Percy and thus could claim descent not only from the Percys also from the Nevills and thereby, through Joan Beaufort, from John of Gaunt and the Plantagenet kings.

William Sayer died at the age of 28 in 1531. He had survived his father by less than a year and, like him, was buried in the church of the Blackfriars at Yarm. His son and heir, John, although still under ten, was forthwith married to Dorothy, daughter of Sir Ralph Bulmer. There is some uncertainty as to the date of her birth, but she was probably a little older than her bridegroom. Betrothals in those times often took place with one or both parties hardly out of the cradle. The church tolerated child marriage on condition that the principals could repudiate it on coming of age, which then meant fourteen for a boy and twelve for a girl. In this case however, the marriage contract entered into in 1521 with the object of uniting the properties of the two families remained unbroken.

Like her mother-in-law, Margaret Fairfax, Dorothy was a descendant of the Plantagenets and also had the Fauconberg and de Brus families among her ancestors. The first de Brus came to England in about 1088, receiving from William II extensive grants of land in the North, including the Lordship of Yarm.

Dorothy Bulmer's mother was born Ann Aske and had inherited the manor of Marrick in Swaledale. She also had the Aske portion of the manor of Colburn near Richmond, and these properties came into the hands of John and Dorothy Sayer. Other lands had come to the Sayers by marriage or inheritance in previous generations so that by this time their possessions, though scattered, were quite considerable; but their undoubted prosperity was already being threatened by a gathering storm that was destined to have a profound effect on their family.

The Pilgrimage of Grace

The religious upheaval known as the Reformation may be said to date in this country from 1534 when Henry VIII repudiated the Pope's authority and caused Parliament to declare him Supreme Head of the Church in England. The seizure of monastic property followed. This provoked an insurrection known as the Pilgrimage of Grace, which broke out in 1536 under the leadership of Robert Aske, a kinsman of Dorothy Sayer's mother. His followers undertook to be faithful to the King’s issue and noble blood, to preserve the Church from spoliation and to be true to the Commonwealth. They demanded the destruction of the heresies of Wycliffe and Luther, the restoration of the Pope's spiritual authority and the confirmation by Act of Parliament of the rights and privileges of the Church. With over 30,000 supporters Aske gained control of all the region between Hull and Newcastle, reinstating dispossessed monks and nuns and trying to obtain restitution of the Church's property; but finally, in 1537, Aske was arrested and by order of the King was left to die of exposure, in a cage suspended from a tower at York.

Dorothy's uncle, Sir John Bulmer, was attainted for his share in the Pilgrimage of Grace, and was hanged at Tyburn in May 1537. On the same day his second wife, Margaret, a natural daughter of the Duke of Stafford, was beheaded, or according to another account, burned at Smithfield.

During Henry's reign the Church remained essentially Catholic in its observances, but the suppression of monasteries and chantries continued, and the translation of the bible and the liturgies into English was pressed forward under Cranmer's guidance. After the accession of Edward VI the movement towards Protestantism gathered impetus: clergy were allowed to marry, the use of the new English prayer book was enforced, and the old rituals and observances were gradually suppressed.

In Yorkshire and the feudally-minded counties of the North the Reformation was accepted far more reluctantly than in the South, and the Sayers of Worsall were prominent among the north-country families who refused to change their religion or to attend the services of the new Protestant Church.

Troubled and uneasy as were the times in which John and Dorothy Sayer lived, they could hardly have foreseen that the bitter conflict between the old religion and the new, and their descendants persistent recusancy would bring the family to the brink of ruin less than a hundred years later.

John Sayer and the Catholic Rebellion

The brief reign of Mary Tudor halted the progress of Protestantism, and the early years of Elizabeth's reign were notable for the leniency shown towards Catholics. It was a privilege of the nobility not to be interfered with in religious matters. Many Catholic gentlemen, such as John Sayer, maintained private chaplains. It is, indeed, recorded that the little chapel near Worsall manor house was served by John Sayer's chaplain, who received household wages. Parish clergy in the 16th century were very poorly paid, so that a priest in a family living or a household chaplain was glad to increase his stipend by acting as a bailiff and secretary to the Lord of the Manor and as tutor to his children.

Every county had its recusants - those Catholics who refused to attend the services of the Church of England - but absentees were merely fined a few pence for each offence. Unfortunately, Catholics had far greater trials in store for them later in the reign.

In 1564 Archbishop Young of York reported that, of sixteen active Justices, six were "no favourers of religion" (i.e. of Protestantism) and should be replaced. John Sayer was one of the six but was nevertheless still a Justice six years later. Sir Thomas Gascoigne, Vice-President of the Council of the North, accounted him "a moderate Papist", and it certainly says much for John's loyalty to the crown that, despite his religion, he was made one of the Queens Commissioners appointed to deal with the aftermath of the abortive Rebellion of the Northern Earls in 1569. This Catholic uprising was in support of the cause of Mary Queen of Scots, and after it had been quelled about three hundred of the participants in County Durham and many others in Cleveland were executed. Among them was John Sayer's first cousin, Robert Pennyman, who was hanged at York.

John Sayer's eldest son - another John - caused his father no little embarrassment at this time, for the young man had sided with the rebellious Catholics and was a gentleman in attendance on the Earl of Northumberland. Thus we find Sir George Bowes - John Sayer's fellow Commissioner - writing in some urgency to the Earl of Sussex, the Lord president of the North, from Barnard Castle on 17th November 1569 in the following terms:

"Yesterday, Francis Norton, with the number of one hundred horsemen, hath entered John Sayer's house at Worsall and therein taken his son, also some portion of armour, which is not great, but much discomforteth him for his son."

Even today, upwards of 400 years later, it is not difficult to picture the horsemen clattering away with their prisoner up the narrow, tree-lined lane that still leads from the manor farm to the Yarm Road. Young John Sayer, after being imprisoned first at Carlisle and then at Durham, was finally extricated on payment of a fine of £500 by his father. This was a considerable sum in those times, probably equivalent to the parents' total annual income.

Yarm Friarage

It was the elder John who acquired the house at Yarm that became known as the Friarage. It had formerly been a Dominican Friary, founded about 1260 by Peter de Brus. It was surrendered to the crown in 1538, when the prior, five priests, six novices and two servants - all who remained of the community - were turned adrift without pensions. The Deed of Surrender, with its seal attached, is in the British Museum. The house and its fifteen acres were sold by the crown to Simon Welbury and Christopher Morland in 1553 for £79 10s. These two yeomen may have bought the Friarage as an investment or as agents for John Sayer, who took possession very soon afterwards. He would naturally have been attracted by the property, partly because his father and grandfather had been buried in the Friars' church and partly because it was in the enclave of High Worsall on the southern outskirts of Yarm.

The purchase of this property was the nearest approach that the Sayers of Worsall ever made to becoming townsfolk. They still had their manors and their farms but, as it turned out, the house at Yarm was to prove a very useful acquisition; it was roomy enough to accommodate a large number of people, and for more than a century various Sayer families and relatives were to find it convenient to make their homes there.

John Sayer died in 1584 aged sixty-three and left a family of five sons and two daughters. The eldest son, John, was born in 1545. He married Frances, daughter of Sir George Conyers of Sockburne, when he was no more than seventeen and seven years later, as already related, was involved in the Rebellion of the Northern Earls. He lived through six reigns; when he was born Henry VIII was still on the throne and when he died aged ninety Charles I had been reigning for ten years. Throughout his long life the religious atmosphere of the country was always tense and often extremely embittered, but his adherence to the old faith never wavered. This was a decisive factor in shaping the future of the family. The status of the Sayers would have been very different in the 18th century if they had not been so uncompromising in their religious convictions during the preceding hundred and fifty years. John was without a doubt a far more ardent Catholic then ever his father was.

The Jesuit Mission

Although the position of Catholics in the opening years of Elizabeth's reign was by no means insupportable, there were marked changes after the election of Pope Pius V in 1570. This brought with it much a more hostile papal policy towards England. The new Pope decreed it to be a mortal sin to attend Protestant services, and declared Elizabeth herself to be excommunicate, deposed, a heretic and a bastard. English Catholics thus found themselves in a dilemma; they had to be traitors either to their Queen or to their religion. But John Sayer, riding over his scattered lands in Teesside, does not seem to have been unduly concerned; he acted on that useful piece of advice found in St Matthews Gospel "Render therefore unto Caesar…..". In short, he was prepared to be a loyal subject of his Queen in all matters - save religion.

Jesuit priests, returning by stealth from continental seminaries, now began to flit around the country, preaching and celebrating Mass in secret and recalling Catholics to obedience to Rome. Nearly 300 Jesuits were hanged as traitors during the last 30 years of Elizabeth's reign - about the same number of Protestants had been burned as heretics in 3 years under Mary - and many Catholics died in prison. Nethertheless, the Jesuits continued to have enough success to alarm the Government very thoroughly, so that anti-Catholic legislation became increasingly severe.

John Sayer naturally sympathised with the Jesuits religious aims and was willing to risk giving them a measure of practical assistance. In 1597, for instance, Thomas Palliser, a missionary from Valladolid in Spain, having escaped from prison in Westminster, headed straight for the North Riding and for a short time was harboured at Worsall. He was captured later and executed in 1600. In the following year the Sayers' manor house at Marrick, which had been standing empty among the lonely slopes of Swaledale, sheltered Anthony Holtby, a recusant kinsman of father Richard Holtby S J. It is possible that the house was then being used by the Jesuit organisation as a base where missionaries could obtain money, books and information and find a safe resting place.

As early as 1581 the Government had made it a matter of high treason to leave the Church of England, harbouring a priest became a felony and anyone saying or hearing Mass was liable to a heavy fine or imprisonment. Under laws passed in 1586, recusants could be fined as much as £20 per lunar month (ie. £260 per year) or risked the possible seizure of two thirds of their property. After this date there was naturally a marked increase in the number of "Church Papists", that is, Catholics who attended church merely to avoid being fined, taking no part at all in the service.

Women recusants outnumbered the men, either because of their greater natural piety or because they lived longer. They were not liable to imprisonment and, having usually no property of their own that could be seized, constituted a thorny problem. In many cases the head of the family would go to church for appearances, leaving his wife and children at home. The children of Catholics had to be either taught at home by stealth or else sent abroad for education in defiance of the law. At one stage Parliament proposed that such children should be taken from their parents and brought up as Protestants, but to this the Queen would not agree.

John Sayer, Recusant

It was in 1586 that John Sayer first became a convicted recusant. He was able to retain his properties simply because he elected, and could afford, to pay the maximum annual fine. The Recusant Exchequer Rolls for 1592-3 reveal that John Sayer had not attended the parish church at Worsall or any other place of worship for over 16 years and that he was making a yearly payment to the Treasury of £260. It is also recorded that in 1595 John Sayer of Worsall, indicted recusant, was a prisoner in the house of Alderman Richardson of York, paying £20 per four-weekly month, and further, that he had lands worth £500 a year. It seems therefore that he was being deprived of over half his income.

In 1628 he paid only £210 instead of the maximum and thus became liable for the first time to the seizure of some small part of his lands. In the following year, as we shall see, he made over all his property to his nephew and heir-at-law, Lawrence Sayer.

It is worth remarking that in 1593, when exchequer receipts from fines were £6,610, more than half the total - £3,380- was paid by only thirteen recusants, John Sayer of Worsall being one of that number. All the thirteen, except Sir Thomas Tresham of Northamptonshire, were esquires, influential locally and, by Elizabethan standards, men of considerable wealth. We know that five or six years earlier John Sayer gave £100 towards the defence of the country against the Spanish Armada - one of the highest contributions from Cleveland. This was a prudent step as well as patriotic, an open recusant was well-advised to demonstrate his loyalty to the crown during these troubled times.

It would be interesting to know how much the various sums of money mentioned above would mean to us today, but it is difficult to come to any definite conclusion. It has been suggested that the purchasing power of the pound was ten to fifteen times greater under the Tudors than in 1940, and according to a later writer, it may have been sixty times greater than in 1962. But as there was a continuous rise in prices between 1520 and 1630, amounting possibly to as much as one hundred percent, no fixed standard for comparison exists. Nethertheless some idea of the impact of fines on recusants can be gained from Thomas Wilson's 1601 survey of late Tudor society. In this he enumerates the various classes below the nobility and gives the approximate income of each group:

Knights, numbering about 500; their incomes between £1,000 and £2,000 per annum;

Esquires ("gentlemen whose ancestors are, or have been, knights, or else they are the heirs and eldest of their houses") numbering about 16,000; their incomes up to £1,000 in and near London but often not more than £300 - £400 "northward and far off";

Gentlemen, unnumbered; an example taken of 310 landed gentry in Yorkshire and Norfolk:

20 with incomes between £300-£400;

40 with incomes between 100 marks and £100;

50 with incomes between £30 and £50;

200 with incomes between 20 marks and £20.

Yeomen; many of this class, benefiting by having long leases in a period of rising prices had incomes between £300 and £400, greatly exceeding in wealth many of their social superiors; Husbandmen and labourers; an unnumbered class of cottagers, copyholders, and tenants-at-will on their lords' demesnes; some fairly prosperous, but "the poor sort working by the day for meat and drink and some small wages".

From that table it will be seen that no recusant below the degree of esquire could possibly have paid £260 annually in order to retain his estates.

The Household at Worsall

By his marriage with Frances Conyers John Sayer received the Conyers' portion of the manor of Colburn, having already inherited the Aske third on the death of his mother. This was the last important piece of property to be acquired by the Sayers. John Sayer esquire, of Worsall, Preston, Yarm, Marrick and Colburn is in fact the representative of the family at the peak of its prosperity.

A certain amount is known about his family and domestic affairs. He and his wife had no children, and after her death in 1585 Agnes Westhorp, "Gentlewoman, supposed to be rich in monies", kept house for the widower. This lady was a granddaughter of John's great aunt Jane, who married Hugh Westhorp of Cornburgh.

In 1595 the household at Worsall included Elizabeth, the wife of John's brother William. That couple seem to have been living apart, for the recusancy records state that Jane Tunstall, Elizabeth's widowed mother, had remained with William Sayer but that Elizabeth, who had an annuity of £20, sometimes went to stay at Preston, which may have been where William lived.

A list of "Yorkshire papists" compiled in 1604 shows that besides "John Saier esquire, a Recusant a long tyme" and his sister-in-law Elizabeth, who was by then a widow, Great Worsall was sheltering John's brother Richard and Richard's wife Ellen. Richard had married Ellen Busby shortly before 1595. He was by then a householder in Yarm, and it was reported that he and his wife both absented themselves from Yarm Church and that in the opinion of the churchwardens he was not worth above £5 in goods. Richard died in or before 1610, after which, and at least until 1616, the recusancy records of Yarm Quarter Sessions show that John Sayer was providing a home at Worsall for Richard's widow as well as William's.

John had two other brothers, George and Thomas, and also two sisters. George Sayer died at Yarm in 1609, leaving an only child Dorothy, who later married William, son of Sir Bertram Bulmer of Tursdale. Thomas is mentioned in the 1612 Visitation but nothing else is known of him. The two sisters both married and had several children. It is safe to assume that every member of the family was a Catholic.

John Sayer was evidently a man of strong personality. The following permit, for instance, issued at a time when Catholics were forbidden to travel more than five miles from their homes, show that, besides being keenly addicted to open-air pursuits, he expected - and got - preferential treatment:

"In 1607 licence was granted to John Sayer Esq., a convicted recusant, to pass and repass…. from his houses of Worsall, Colburn and Marrick in the County of York and to any other places within five miles of them; and also, to hunt, hawk or chase his game, he shall fly out of the said compass of five miles and so follow his chase, game, or sport and to go to any hunting matches near the places aforesaid, returning again after his sport ended".

Since Marrick is at least 20 miles west of Worsall, with Colburn lying between the two, he can have had no reason to complain thereafter.

Sayer Properties

Three settlements of property were made by John Sayer. In the first, dated 1597, he settled property on two nieces and a nephew, to wit: Dorothy, daughter of George Sayer; Dorothy, daughter of William Sayer, and Lawrence, the then infant son of Richard Sayer. No details of this Deed are known, but it is referred to in the second settlement, made in 1610, by which time William's daughter had become the wife of John Errington. John Sayer conveyed to four trustees the following properties: the manor and lordship of Great Worsall, the demesne lands and messuages in Colburn, messuages and lands in Kirkby, Stainton, Stainsby, Maltby, and South Kilvington, and one messuage called Hillaye Leys. All these were in Yorkshire. In County Durham there were messuages and lands in Preston, Norton, Stockton, Seaton, Hartlepool, and Neasham, with 12 acres of meadowland called Elvetmire in the parish of Egglescliffe, just across the Tees from Yarm.

All these lands were to be held for the use of John Sayer during his life and then to pass to Lawrence and his male heirs, and in default of them to Dorothy the daughter of George, and in default of her to Dorothy, the wife of John Errington.

Finally in 1629, John Sayer, at the age of 84 compounded by Lawrence Sayer for all his lands, messuages and manors for the total rent of £260 per annum. They consisted of Worsall, Marrick, Colburn, Stainton, South Kilvington, Maltby, Tirrington, Firby, Richmond, Faceby, Carlton, Yarm, Naby and Picton in Yorkshire and Preston, Stockton, Norton, Seaton, Neasham, Hartlepool, Fishgarth and Silksworth in County Durham.

John Sayer also engaged in lead-mining, which had been carried on among the Yorkshire Dales since Roman times. There were profitable lead-mines on the Marrick estate, and these John settled on his niece Dorothy, who in about 1630 had married William Bulmer. His family too had started lead-mining, and the Sayer-Bulmer complex of mines, making an annual profit of about £1000, was probably the largest in Yorkshire.

William Bulmer, like John Sayer, was a recusant; but whereas the older man had become one of the wealthiest squires in the North Riding, Bulmer seems to have had less ability and also was probably hampered by financial problems inherited from his spendthrift father, Sir Bertram. This, coupled with the anti-Catholic measures of the Commonwealth's government, meant that by 1671 the Bulmers' were forced to sell the mines as well as the manor.

John Sayer's Will

John Sayer signed his will on 21st July 1630. It is a very comprehensive document and not only throws light on the family's affairs in general but also illuminates the character of the aged testator. He emerges as a staunch Catholic, a good landlord and the absolute and unquestioned head of a family whose welfare he had very much at heart. Even at the age of eighty-five he was still keeping an expert eye on his properties and affairs.

After the usual pious preamble which concludes by directing that he shall be buried at Marrick as near his wife as possible, he allocates gifts of money to poor Catholics and to prisoners of that faith at York, Durham and Sadberge. His debtors are relieved of their obligations and his tenants are not forgotten. He himself being childless and having outlived all his brothers and sisters, he takes care that every one of his nephews and nieces, as well as their children, shall benefit.

Most of the bequests are in the form of money, but there are also such gifts as bedsteads, his best horse, the two next best and "a jewel called an amitist". Two great nephews and a great-niece are allotted £50 each, to be used to their best advantage, while they are still minors, and one of them - John, the son of Lawrence Sayer - is given, among other things, all the lead in the smelting house at Marrick. The proceeds are to go towards building a new house for him.

John, son of Francis Sayer, deceased, is left a house and 4 oxgangs of land in Yarm. Rents from land at Picton are to be devoted - by Lawrence - to a school and almshouses. The smithy at Colburn is left to his niece Dorothy and her husband William Bulmer on condition it remains in use as such for the convenience of the tenant of the manor house. Dorothy and William are also enjoined to provide Lawrence Sayer during his lifetime with a buck in summer and a doe in winter from the Marrick estate. All the corn at Worsall, sown or growing, is left to Lawrence. Elizabeth, the widow of George Sayer, having surrendered property in Lincolnshire, receives a farm at Colburn as an equivalent and also four milk kine. John Errington, who had married William Sayer's daughter Dorothy and was now a widower, is confirmed in his tenure of 8 oxgangs of land at Preston and receives special consideration because of the great expense he has incurred in giving his children a good education.

The general disposal of John Sayer's manors and lands had already been settled by the Deeds of 1597, 1610, and 1629 but his goods and chattels still had to be distributed. Accordingly the contents of Marrick house are left to Dorothy Bulmer and those of Worsall, with all its farming equipment, to Lawrence. Goods and chattels at Colburn are to be shared between them. The residue of the personal estate is divided in equal shares among Dorothy, Lawrence and Errington.

A codicil was added in 1632 leaving a share in a farm at Marrick to James, son of Francis Sayer deceased and pointing out that the sheep on Shaw Moor should be regarded as part of the goods and chattels - Lawrence and Errington were to have six score each and Dorothy Bulmer the rest.

The executors of the will were Lawrence Sayer and George Meynell (called "cousin"); its supervisors, Anthony Metcalfe (also a cousin), Sir William Lister ( a nephew by marriage), Thomas Crathorne and John Witham.

A Knighthood Refused

It appears that almost at the end of his life John Sayer may have declined a knighthood. Certain feudal enactments had been revived by Charles I in order to raise money, and after 1630 a fine was entailed by failure to comply with the law which had formerly required all owners of estates above a certain annual value to be knighted. A manuscript note of unknown origin has been found to the effect that in about 1632 John Sayer compounded against taking a knighthood by the payment of £75.

After 1635 - Lawrence the Elder

In 1635 the old Squire died, aged ninety, and Lawrence Sayer, then thirty-eight, succeeded to his uncle's estates, with the exception of such property as had been settled on the Bulmers and Erringtons. John Errington, incidentally, was living at the Friarage in 1632 at a rent of £10, and there is some evidence that it was also the home of Lawrence and his family.

After 1635 Lawrence's manor of Worsall was occupied and managed by John, the son of Francis Sayer. Rather confusingly, Lawrence's own eldest son, born about 1620, was also named John. Both are referred to in old John Sayer's will and also in the indenture of 1637. The former is described in the recusancy returns of 1637 and 1641 as John Sayer, gent., of High Worsall. His wife Margaret was also a recusant. He died at Worsall in 1658, and his grandson Robert was born there in 1660; but the family moved, probably to Stockton, soon afterwards, for no Sayer paid Hearth Tax at Worsall in 1662.

The other John Lawrence's son, is mentioned in Don Huddlestone's Obituaries, where it is stated that, according to Blount's "catalogue of Catholics who died and suffered for their loyalty", Lt Colonel John Sayer of Worsall was slain at the battle of Naseby in 1645. It is added that Colonel Sayer married Elizabeth, the third daughter of George Preston Esq. A slightly different version, found in a handwritten pedigree dated 1763, states that it was in 1647 that John Sayer of Worsall died of a mortal wound received in the service of King Charles; but it agrees that he married Elizabeth Preston.

Catholics and the Civil War

With the accession of Charles I the situation of Catholics improved a little, and Mass could be celebrated more or less openly; but even so, the fines paid by recusants, though fluctuating a good deal, reached £32,288 in 1640, when acknowledged Catholics represented no more that one eighth of the population.

In the Civil War, which broke out in 1642, fighting took place on Teesside more than once. In 1643 there was a sharp engagement with heavy loss of life at Yarm bridge when the passage of a Royalist convoy of arms and ammunition moving south from Newcastle was disputed by the Parliamentarians.

Parliament continued to hold Yarm during 1643 with a garrison of four hundred or more but the town was retaken by the Earl of Newcastle, who was then able to recover all the northern counties, except the Hull area, for the King. By November 1644, however, after their victory at Marston Moor, the Parliamentarians were masters of all the eastern half of England from the Channel to the Scottish border.

During the war the Catholic religion was openly practices in the North and West, and no penalties were enforced. Catholics had naturally sided with the King: they made up two thirds of the Earl of Newcastle's army, and between 35% and 40% of the Royalist officers killed were Catholics.

After the King's capitulation the inhabitants of County Durham and Cleveland protested to Parliament against the heavy burden imposed upon them by the presence of English and Scottish troops who had not been disbanded, and in December 1646 it was agreed that on payment of £200,000 the Scots should quit all their strongholds and other quarters south of the Tyne.

Sequestration during the Commonwealth

Cromwell executed very few Catholics but they were excluded from the life of a community and were regarded with great hostility. Estates were now sequestrated on the grounds of delinquency, the most serious cases being those of "traitors", that is, militant Royalists. These were blacklisted and their property was confiscated. It was then put up for sale by a body known as the Treason Trustees. About a dozen North Riding Catholics came into this class, Lawrence Sayer among them. His military record is not known in detail but in the eyes of the Government it was bad enough for him to be sold up completely.

The manor of Marrick had already passed out of the family by the marriage of Dorothy Sayer and William Bulmer. Lands at Colburn, Stockton, Egglescliffe and elsewhere had been forfeited, and now Lawrence's chief remaining properties - Worsall, Preston, and the Friarage - were to be lost. They were bought during the Government Sales of 1653 by one Gilbert Crouch, a London lawyer. Crouch had extensive Catholic connections in the North and is often mentioned at this period, for he was one of the foremost collusive buyers of recusants' estates. He was undoubtedly of invaluable assistance to his unfortunate clients. There would be some arrangement whereby Crouch and the previous owner of the property both contributed to its purchase from the Treason Trustees and shared the income thereafter. Such expedients were not infrequently resorted to by Catholics so as to avoid to some extent the crippling effects of the penal laws. Indeed, it is known that, although Crouch was the official owner of the Friarage for some twenty years, the Sayers were occupying it, or parts of it, all that time.

Lawrence himself was probably one of the recusant delinquents who fought in the second phase of the Civil War as well as the first. He was officially described as "a dangerous Papist in arms". With his companions Peter Metcalfe and Robert Barry he devoted himself to a life of conspiracy against Cromwell's Government and at one stage he seems to have been little better than an outlaw. The situation of his family was not enviable; in fact, by 1650 their plight seems to have been desperate, for a petition made by his wife Elizabeth on behalf of herself and thirteen children reads as follows "….. her husband's estate is sequestrated for his recusancy and delinquency and she hath only a fifth for their maintenance which is now denied her without your order. She prays for the allowance of the fifth part, being else destitute of all relief". Fortunately, this plea was granted. The thirteen children included grandchildren and probably some other other young relatives, as well as Elizabeth's own younger offspring.

In July 1652 Lawrence appealed - without success, it seems - against the leasing of two thirds of Colburn manor to Philip Saltmarshe on the ground that his grandfather, his uncle and himself had had quiet possession of the property until its recent sequestration.

The last known reference to Lawrence Sayer is dated 1658, and he probably died within the next two years. It is, however, certain that his eldest son - the Lt Colonel John Sayer already mentioned - predeceased him. For in 1653, the year in which Worsall was put up for sale by the Treason Trustees, we find an Elizabeth Sayer, described as the widow of Lawrence's son and heir John, claiming one third of the manor under an indenture dated ten years earlier - probably a marriage settlement. Elizabeth's claim was disallowed, however, and the purchase took place.

Lawrence Sayer the Younger

In default of John, the second son, Lawrence the younger, born about 1632, became the head of the family. In 1658, while living at the Friarage, he signed on his father's behalf the Deed of Award at the division of the Town Fields of Yarm - an award by which Lawrence Sayer, Christopher Lister and Gilbert Crouch received 56 ½ acres known as Spital Flats adjoining the Friarage grounds. Lawrence also had four burgages in Yarm and the "farm" of the parish tithes on a long lease from the Archbishop of York. In Surtees' "History of Durham" he is described as "Lawrence Sayer of Worsall, 1660", from which it may be inferred that his father had already died. In that same year Lawrence surrendered his rights in some property at Preston to Gilbert Crouch.

Strangely enough, Lawrence is not recorded as a recusant; but there is little doubt that he was a Catholic, if only a lukewarm one. His youngest sister, Cecily, who was born in 1643, married Nicholas Mayes, a Catholic merchant of Yarm, in 1666. Four years later Mayes became the owner of the Friarage, letting part of it to Katherine Sayer, Cecily's elder sister. She died unmarried in 1678 and left a moiety of her lease of the house and garden and part of the adjoining Spital Flats to her nephew Nicholas, Cecily's son.

Lawrence Sayer borrowed heavily in an effort to buy back some of the family's properties but failed to meet his obligations. Consequently in 1670 we find him associated with Crouch (for the last time) in selling not only the Friarage but also the Worsall estate and lands at Egglescliffe and Neasham. It may be thought that he might have farmed the properties he leased from Crouch sufficiently well to improve them and in time to pay off his debts, but either through lack of ability or through ill fortune he was unsuccessful. He was still a freeholder in Aislaby, County Durham, in 1684 but was then living in Ireland. It is possible, however, that he returned to England before 1690, because the marriage of a Lawrence Sayer and Catherine Burdon took place in Durham cathedral in that year. Their son Robert, of whom more is known, was born in 1693.

Decline and Dispersal

Towards the close of the seventeenth century the Sayers longstanding connection with the Manor of Worsall and the Friarage had come to an end, and the old family may be said to have disintegrated. Owing to the recusancy fines and later to the recalcitrance of the older Lawrence and the failure of his son, the family had become impoverished and virtually landless.

Nethertheless, at various periods from 1600 onwards there were several Sayer families scattered across the North Riding. Some of these groups were small and isolated, others remarkably extensive. All of them were of somewhat lower status, socially and financially, than the Sayers of Worsall. They were tenant farmers, millers, weavers, and suchlike, although a few, like Ambrose Sayer who died in 1735, his brother James, a recusant, and his son Mark who farmed at Great Ayton, retained the "Mr" of gentility.

Two junior lines, originating in the 1550s stemmed from the Sayer family of Worsall. One was founded by William Sayer of Rudby, who was mentioned in the will of his uncle Leonard Sayer in 1559 and was a first cousin of John Sayer of Worsall (1521-1584). William died in 1588 and his wife Agnes two years later. Their great-grandson was John Sayer of Rudby, of whom more thereafter. His marriage linked two lines.

The other junior line was headed by Francis Sayer. It is recorded that in 1552 John Sayer of Worsall, gent., and his brother Francis Sayer of Marrick, yeoman, were sued - unsuccessfully - for depasturing cattle on land claimed by Avery Uvedale. During the hearing it was established that Francis had been a yearly tenant of a property known as Marrick Park since 1550 and that his landlord was a Sir Ralph Bulmer, the father of Dorothy Sayer.

Francis made his will in 1585. In the following year his son - another Francis - and his son's wife, Ann, were listed as recusants. They were then living at Yarm though still holding the Marrick Park property. In 1595 it was reported that "Ann, wife of Francis Sayer, has never attended Yarm Church since she and her husband came to live at the Friarage, but Francis himself is no recusant". This seems to indicate he was a "Church Papist" at this period. In 1604 he was described as "gentleman , poore, a non-communicant", and either in that year or earlier the family were deprived of Marrick Park. The reason can be found in a letter from Archbishop Hutton of York to Lord Dorset, the Treasurer of the Recusancy Fines in which the writer gives the names of five convicted recusants, Francis Sayer among them, whose confiscated estates King James wished to grant to Dr. Martin, the Queen's physician.

The Sayers of Rudby

Francis and old John Sayer of Worsall (1545-1635) were first cousins, and he was one of the trustees of John's 1610 Deed of Settlement. He was again named as a recusant at the North Riding Quarter Sessions in 1616 and had died before John Sayer made his will in 1630. One of his sons, John Sayer, gent., of Worsall, has already been referred to. Another son, Richard, became a Jesuit priest and in 1624 at the age of twenty six joined the College at Watten in Flanders. His name in religion was Richard Stanley. Their eldest sister was named Helen and in 1607, when twenty, she married James Smith of Snainton. They had eight children and one of the four daughters, Susan, who was born in 1615, married the John Sayer of Rudby mentioned earlier.

Rudby, or Hutton Rudby, lies about five miles south-east of Worsall and was always a strongly Catholic area. This may have been due to the influence of the Mission at Crathorne nearby. Archbishop Herring's Visitation in 1743 shows that, out of forty-nine families at Crathorne, twenty-two were Catholic and that there were twenty-three Catholic families in Hutton Rudby.

Sayer entries in the parish registers begin before 1600 and continue for eight generations into the early nineteenth century. It became a very widespread group, splitting up into a large number of related families. There were doubtless a great many Catholics among them who were not noted on the registers.

Susan Smith, the granddaughter of Francis Sayer, became the second wife of John Sayer. She was a recusant in 1674 and had a family of nine children, one of whom was John Sayer, born in 1647. Both he and his wife Elizabeth were recorded as recusants in 1674, 1685, and 1691. Their eldest son, James Sayer of Hutton Rudby, was also a recusant in 1691. Fourth in descent from this man was Edward Sayer, my grandfather. He was the first of his line to leave Yorkshire, coming to London in 1837, and living there until his death in 1897. Neither he nor his parents were Catholics; nor were, or are, any of his descendants as far as I know. His great-uncles James and William were among the last Sayer burials in Rudby. Both died in 1815.

In 1745 three Sayers of Rudby, Joseph, Thomas, and James, refused to abjure their faith but agreed to abide by the anti-papist laws. Thomas may have been he who figures as a Catholic in the register of burials in 1789. This is the last reference to Catholicism among the Sayers of the North Riding.

Worsall

When visited in 1973 the area known as High Worsall contained no more than two farmhouses and a few cottages. There was no through road. Manor Farm, a relatively modern building, had replaced the old Manor House, and in an adjacent field various ridges and mounds showed where the houses of a vanished village once stood. The field also contained a wire-fenced graveyard and the remnants of a very small stone-built chapel.

A chapel existed at High Worsall as early as 1204. It was dependent on Northallerton. By 1719 it had become ruinous and out of its remains another chapel was built on the same site. This was in use until about 1891, when the combined parish of High Worsall with Low Worsall was formed and the church of All Saints was built at Low Worsall. The little chapel was then abandoned and when it became extremely dangerously dilapidated the roof was removed and the walls reduced to shoulder height. The old chapel was "remembered" by an annual open-air service held there until 1921. The graveyard, neglected and wildly overgrown is still officially available for burials.

Worsall was bought by the church commissioners in 1938.

Hillilees

The farm of Hillilees was one of about twenty minor properties and pieces of land owned by the Sayers in the early seventeenth century. It is referred to in John Sayer's 1610 Deed of Settlement as a "messuage called Hillaye Leys", and was sold by Lawrence Sayer to his tenant John Clifton in 1642 for £600.

There is a persistent tradition that Hillilees was once a "nest of Papists", and it is a fact that in the early 18th century it was described in the records of the Quarter Sessions as a Papist estate.

The farm, owned in the 1960s by William Bainbridge, is on Staindale Ridge, the highest part of Low Worsall Moor.

Marrick Priory

A religious house for Benedictine nuns, Marrick Priory was founded by Roger de Aske in the 12th Century. Its church, dedicated to Saint Andrew, was shared by the nuns and the villagers and on the suppression of the Priory in 1540 continued to serve the parish. It stood until 1811 and was then rebuilt on a smaller scale using the old materials. Only the tower was left untouched, though a fragment of the mediaeval chancel could be seen to the east of the newer building. By the late 1960s all the memorials, excepting the tombstone of a nun, and every scrap of the furnishings had disappeared, and the church was a derelict shell. A farmhouse standing parallel to its southern side and some stone-built outhouses adjoining the tower probably incorporated parts of the Priory buildings. There was no other trace of them. The burial ground to the north of the church was merely an enclosure of rough grass. It had been cleared of its gravestones, some of which stood against the boundary wall and the side of the church. The oldest stones, very crudely inscribed, dated from the early eighteenth century. Either here, or more probably, within the church, John Sayer, lord of the manor, was buried in 1635.

Yarm Friarage

In 1670 Lawrence Sayer and Gilbert crouch conveyed Yarm Friarage to Nicholas Mayes, a Catholic merchant of Yarm, who married Cecily Sayer. Their elder son, John, registered the estate in 1717 as worth £100 per annum. This registration was for taxation purposes and was required only of Catholics.

In 1735 the Anglican curate at Yarm reported as follows: "There is a reputed Popish priest who constantly resides in Mr Mayes family; his name is Syddal. Mr Mayes' house is the place of resort where great numbers of Papists assemble every Sunday, and there Mass is understood to be performed".

John Mayes married Mary Meynell, and when their daughter died childless in 1770 the Friarage passed to the Meynell family, also strong Catholics. During the next five years Edward Meynell rebuilt the house in its present handsome form, incorporating the foundations and cellarage of the original Friary and also using material from the ruins of the Blackfriars church.

The premises were occupied by tenants of the Meynells from 1865 until 1957. In that year the engineering firm of Head Wrightson bought the Friarage, which thus for the first time in seven hundred years passed out of Catholic ownership. During 1966 the house was sumptuously renovated to accommodate the Company's Head Office Staff.

Nothing of the old Friary or its church remains above ground. The site of the church was excavated in 1930 by one of the Meynell tenants, but the foundations were, regrettably, covered up again before the ground plan had been plotted by experts. Some human skeletons, judged to be about 5 or 6 centuries old, were suitably re-interred and a cross erected over their grave.

The buildings forming a northern wing of the house appear to be of an earlier period and probably date from the time of John Mayes ownership. On the upper floor of this wing is a large room with a curved ceiling clearly used as a private chapel. In 1959 three carved wooden panels that had formed the reredos of a removable alter were found in an attic, and in a masked cupboard in the chapel-room were some religious books; six of these, of dates between 1618 and 1783, are of considerable value.

The oldest structure in the Friarage grounds is an octagonal dovecote built of brick and stone in the late Tudor or early Stuart times, presumably by one of the Sayer owners.

Sayer Families from Teesside

The pages that follow contain accounts of those Sayer families that can claim to be descendants or kinsfolk of the Sayers of Worsall, or at least are known to have originated on Teesside. These families have been given the following descriptions: "Richmond, Surrey", "London" and "Middlesex", denoting where each settled after leaving the North. There are also accounts of two other Sayer families, one first heard of at Croft-on-Tees and the other at Lartington, near Barnard Castle.

These separate narratives are prefaced by some notes on the position of Catholics from the Restoration onwards and by a general description of conditions in the North Riding during the 18th century and of the Sayers who lived there.

Catholics after the Restoration

With the return of Charles II the treatment of Catholics became more lenient; so much so in fact that Protestant suspicion and resentment were aroused and gave rise to Titus Oates 'Popish Plot'. As a result of this, there were a number of executions, Catholics were excluded from both Houses of Parliament and country gentlemen, especially in the North, were debarred from all Government posts.

James II did his utmost to have the Catholic religion legalised but after he was deposed in 1688 every possible obstacle was put in the way of Catholics educating their children in their faith, inheriting or buying land or holding any public office. It was not until after the collapse of the second Jacobite rebellion in 1745 that Catholics at last began to obtain some slight relief from some of the handicaps under which they had lived for so many years.

Among the recusants of the North Riding in 1690 were James Sayer of Hutton Rudby, his wife Elizabeth and their son James, also of Rudby. Two of the elder James brothers, Francis and Robert and their sister Susanna of Rudby were also listed. No Sayers in this area are known to have been recusants after that date although two at Skelton are mentioned in 1733-1735; nor are any Sayers found among the North Riding registrations made under the Act of 1715 whereby every Catholic owner of property was required to declare its annual value for land tax purposes. It follows therefore that such Sayers as were still Catholics were not owners of property. Some at least are known to have held to the old religion but the total number of Catholic Sayers found in Archbishop Blackburnes's Visitation of 1735 and in Fr. Hervey's registers of about the same date was something under thirty including children. All these lived in Cleveland; about a third of them near Rudby.

In 1745 among the Catholic Sayers were Thomas, Anthony, George and James of Moorsholm near Guisborough, Joseph and Thomas at Rudby, John at Hutton Rudby and also John Sayer at Stokesley. These refused to subscribe to the Declaration but undertook "to abide and perform the laws" then in force against papists, reputed papists, non-jurors, etc.

Farming and Lead Mining

It has been asserted, probably with some truth, that during the 18th century life in the rural areas and small towns was pleasanter, more prosperous and less subject to outside disturbances and alarms than at any time since the outbreak of the Wars of the Roses in 1455. Thomas Richmond in his "Local Records of Stockton" quotes the following passage written in 1703: "All things was very cheap; butter was but 10/- a firkin [56 lbs]; best wheat 2/6- a bushel, best beef 18d a stone and all things both for back and belly was so cheap as was never known by any now living."

The country south of the Tees – Cleveland and the plain of York – has been called the land of the yeoman farmer and it was here that many of the 18th century Sayers were to be found. Its wide acres, adequately watered and sparsely populated, had become valuable as farming land and as a fattening ground for upland sheep and cattle. The only industry, apart from farming and weaving, that the area had ever known was the manufacture of tiles. To the west, however, among the dales, lead-mining had been carried on since Roman times or even earlier. In 1609 the London Lead Company began mining operations in Teesdale and there was also private enterprise; as mentioned earlier the Sayers and the Bulmers had lead mines near Marrick in the early 17th century. Mining continued on a diminishing scale until about 1913 but all the workings are now abandoned.

18th Century Sayers in the North Riding

The parish registers for Aysgarth, Bowes, Romaldkirk and Rokeby show many Sayers settled in that north-western corner of Yorkshire. The group in the Bowes area was particularly extensive, the entries covering six generations and showing a few links with the Sayers at Rokeby.

Most of the Sayers in this region were farmers but there were a few lead miners (near Aysgarth), an innkeeper or two, some tradesmen and one who appears to have combined shop-keeping with farming. William Sayer was Parish Clerk of Bowes for forty-seven years and after his retirement – he lived on to be ninety – his grandson held the post. There are descendants of the Sayers at Aysgarth and Bowes farming in the North Riding today.

In the late 16th and early 17th centuries there were Sayers living near Barnard Castle.

Turning to the area South of Yarm, three or four generations of a Sayer family can be traced in the Northallerton parish registers between 1680 and 1770. They included James Sayer, labourer, and his son John, a weaver. In Yarm itself the registers have a number of Sayer and Sawyer entries between 1658 and 1862 but these refer only to small isolated groups or to individuals and show little continuity of descent. The same applies to entries in the registers of many other parishes such as Thirsk, South Kilvington, Stokesley and Kirklevington.

The existing parish registers of High Worsall, which are kept in the church of All Saints at Low Worsall, start in 1720. They contain no Sayer entries except the marriages of Martha and Jane Sayer in the last decade of that century. The pre-1720 registers are unfortunately missing. They are said to have been destroyed in a fire and we are thus deprived of evidence that might have shown which members of the family lived there after the death of John Sayer of Worsall in 1635 and whether any of them stayed in the parish after the manor was sold in 1670. No Sayer is found in the lists of tenants of the manor between 1725 and 1800.

The Sayers of Richmond, Surrey

Notwithstanding the loss of the early registers of Worsall, there does exist evidence that the family of at least one Sayer lived in that parish after 1635. This man was John the son of Francis Sayer. In 1610 he had been witness to a deed of settlement made by John Sayer senior, the head of the family, and twenty-five years later had inherited a house and 4 oxgangs in Yarm under the old squire's will . The ownership of Worsall Manor passed to Lawrence Sayer but it seems that the younger John had been the occupier of the estate and continued to manage it, for in the Recusancy returns of 1637 and 1641 he is described as John Sayer, gent, of High Worsall. His wife Margaret, whose maiden name was probably Metcalfe, was also a recusant.

John died in 1658 and his daughter Anne was granted administration of his estate, the widow and son Francis having renounced. As will be seen later, there is evidence that another son, named James, remained at Worsall, and that one of his younger sons, Robert, was born there about 1660. No Sayer appears to have paid Hearth tax at Worsall in 1662, so the family had presumably left the parish by that date. In 1688 Robert Sayer, having sold some land to Sir Marmaduke Wyvill, is described as of Stockton.

The parish registers of that town show the baptisms of Robert's sons: William in 1694 and James in 1695. Robert was buried in 1732 at Marton, a few miles south-east of Stockton, and was survived by his wife Elizabeth - not surprisingly for she attained the age of a hundred and one. Her burial is recorded at Stockton.

Their younger son, James, was apprenticed in 1713 to Thomas Burdus, a Durham attorney. He married Thomasine, daughter of John Middleton Esq. on 29th July 1718 at Durham Cathedral and died at Sunderland in 1736. About twenty-five years later his widow deposed that she had often been told both by her husband and by her father-in-law Robert Sayer, that the latter's father had been named James and his grandfather, John; and further more that both of them had lived and died at Worsall. This statement, which, in default of register entries, seems positive enough, is the authority for the family's connection with Worsall. A handwritten pedigree dated 1763 purports to trace the family's descent from John Sayer of Worsall (1486-1530). Although this is broadly speaking correct, the first half of the document contains several inaccuracies and is of only limited value. The second half appears more trustworthy.

James Sayer of Richmond

The eldest son of James and Thomasine was born at Stockton and when christened there in May 1719 was named after his father. This boy later came to London, was admitted to the Middle Temple in 1758 and called to the Bar in 1760. In 1755 he was living in Essex Street, Strand, and in that year he married Julia Margaret Evelyn at Chelsea Parish Church. Her father, Edward Evelyn Esq. of Godstone, was one of the well-known family that had included John Evelyn the diarist and his wife was Julia, natural daughter of James, 2nd Duke of Ormond.

James Sayer's will shows that Julia Margaret was his second wife. There are indications that the maiden name of the first Mrs Sayer was Beaumont but no other details are known, nor is there any reference to children by that marriage.

In 1765 James was holding the post of Deputy Steward of the Royal Manor of Richmond in Surrey and he later became Steward, a position that he retained until his death in 1799. He was also Deputy High Steward of Westminster and appears to have been a personal friend of George III. He lived at the Manor House, Marshgate – the old name for Sheen Road. The house had been "wayhold of the Manor of Richmond" but it is recorded that the King was so attached to James that as an act of grace he enfranchised the property to him and made it freehold.

James Sayer's daughter, Frances Julia, remained single until she was nearing fifty. She then married the Chevalier Charles de Pougens, a distinguished man of letters , literary counsellor to the Dowager Empress of Russia and a member of the Royal Institute of Paris. The de Pougens lived at Vauxbuin near Soissons where Madame de Pougens, widowed in 1833, spent the rest of her long life. She died in 1850, aged ninety-three and was buried beside her mother in the Evelyn family vault at Godstone. A number of her admirable letters were fortunately preserved; extracts from a series written while visiting Paris shortly before the French Revolution and from a later set describing her time in France during the eventful years of 1814 and 1815 are given in an Appendix later in this document.

Frances Julia's brother, Edward, James's only son, was educated first at Westminster and then at Harrow. He was admitted to the Middle Temple in 1777, becoming a barrister in 1783 and later a Commissioner of Bankrupty. In 1784 he published his "Observations on the Police or Civil Government of Westminster with proposals for their Reform", and in the Dictionary of Living Authors (1816) he is described as a very ingenious poet and an excellent painter. He is also said to have produced a number of admirable caricatures. He never married and when he died in 1834 his estate, estimated at about £5000, was administered by his nephew Robert Sayer acting on behalf of Frances Julia Sayer de Pougens.

Among the papers collected by A.A. Barkas, one time Borough Librarian at Richmond, is a drawing of the Sayer tomb in the burial ground in Vineyard Passage, the inscriptions commemorating seven members of the family. The tomb itself has now disappeared but one of its stone slabs, with the names of James and his son and daughter still legible, is set in the ground near the southern boundary wall.

Robert Sayer the Printseller

James Sayer had a younger brother Robert who was born in 1725 after their parents had removed to Sunderland. Like his brother, Robert Sayer came to London as a young man. Here he established himself as a print seller about 1750, succeeding "M.Overton" who had been carrying on Philip Overton's business at the sign of the Golden Buck on the south side of Fleet Street. The house was later known as 53 Fleet Street. In 1755 he took a partner named John Bennett but from 1784 onwards managed the business alone. He also had premises in Bolt Court, Fleet Street, which are referred to in his will as a manufactory for printing geographical and other maps.

An article on Painting and Engraving by Andrew Shirley in "Johnson's England" contains the following passage:-

"Print shops were the galleries of the ordinary citizen and there he could purchase for a few shillings the portrait of any topical character. Thomas Bowles and Philip Overton were leading publishers of the portrait print but the trade had its pirates too, like Robert Sayer, whose hacks turned out cheap versions of better work; from their large number we can guess the demand."

Whatever his reputation among print sellers Robert Sayer seems to have found the business sufficiently lucrative. His assistants, Messrs. Laurie and Whittle, carried on the business after his death.

Robert Sayer and Dorothy Careless married at Datchworth near Welwyn about 1754. It seems not unlikely that she was of the same family as Colonel Careless who was Charles II's companion in the famous oak tree and whose name the King afterwards changed to Carlos when granting him a special coat of arms. Robert and Dorothy had seven children but their family Bible makes melancholy reading; no fewer than six of those children died in infancy, the only one to survive being James who was baptised at St Dunstans-in-the-West in 1757. Mrs Sayer died in 1774 and Robert then appears to have followed his brother to Richmond where by 1780 he owned the Mews House with a 2-acre field adjoining it, and also a house in the Richmond Hill district.

It was in 1780 that Robert married his second wife, Alice Longfield, a widow . This lady's brother, Mr. Tilson, had bequeathed to her a house near Richmond Bridge, with remainder to a Mrs Peacock. Robert Sayer bought this reversion and the Richmond rate books show that he was assessed at £5.5.0d for this house. By 1790 this had increased to £6.2.6d and an additional assessment of £2.12.6d was made for a wharf and for vaults under the approach road to the bridge which ran directly in front of the home. Richmond Bridge was opened in 1778 and before it was constructed the house would have fronted onto the road leading down to a ferry and the vaults of course would not have existed.

Robert left Bridge House to his widow for her lifetime, and then to his son James, his nephew Edward and his niece Frances Julia successively. In the event it was inherited by James and was in the hands of James's grandson at least as late as 1887. This is shown in a lease of that date from the Commissioners of Richmond Bridge to Lieut-General Sayer for 42 years. The house has now been demolished and its site together with its original garden forms part of a public riverside pleasance.

The Zoffany Pictures

Johan Zoffany, the fashionable German painter, produced three pictures of the Sayer family. The first of these, painted in 1770, shows Robert's son James, aged 13, with his fishing rod, and a very charming piece of work it is.

(James Sayer)

The other two paintings are portrait groups and in the smaller of the two it is clearly the garden of Bridge House that Zoffany has used as a setting. Robert Sayer is seen seated on one side of his second wife and his son James stands on the other. Behind them can be seen the back of Richmond Bridge House and to the left in the distance, is Richmond Bridge. The painter allowed himself some licence in the relative positions of the house and the bridge but contrived a very attractive composition thereby. The date of this picture is probably between 1780 and 1783; that is, soon after Robert Sayer remarried and acquired the house and before Zoffany left England to work for seven years in India.

(Sayer family)

The late Miss Ethel Sayer who owned the pictures in 1930, identified the older gentleman on the left as old Robert Sayer with his niece Frances Julia standing on the right with James Sayer and his wife and baby son Robert. It is now known, however, that old Robert died before his grandchildren were born – in fact before his son had married – and also that James's wife died within a few days of the birth of Robert, her second child. It seems therefore that Zoffany not only introduced a posthumous portrait of old Robert Sayer but very likely one of James's wife as well. If she was painted during her lifetime then the baby she is holding must have been her first son who died in 1796 aged eleven months. If this is the case, it gives a guide as to the date of the work. These discrepancies are puzzling but, when all is said and done, they need not effect one's enjoyment of a very pleasing picture.

The paintings came onto the market in the early 1930s, the smaller group fetching £980 and portrait of young James fetching £1020. The larger family group is in the possession of Sir Reginald MacDonald-Buchanan.

The Duke of Clarence

The 1790 rate books of Richmond show that, as well as Bridge House, Robert Sayer had a house "next above Samuel Pechell's "Going up the Hill", that is, on Richmond Hill, four or five properties above a small side street called the Vineyard. This is the house referred to in the Vestry Minutes for June 1794 "Mr Sayer's house on the hill with a field garden and offices having been let to H.R.H. the Duke of Clarence for £420 ready furnished, resolved that Mr Sayer be assessed for the same for Poor and Highway Rates at £200 p.a.". (The Mr Sayer referred to here must be James; his father had died in the previous January.)

The Duke's address in the Universal British Dictionary for 1791 is given as Richmond Hill. His connection with Mrs Jordan began in that year and he installed her at Petersham Lodge in October. But as the Vestry Minutes shows he continued to rent a number of houses in Richmond itself as well. Mrs Jordan remained at Petersham Lodge until she and the Duke removed to Bushey Park in 1797.

It has long been assumed that the Georgian residence in the Vineyard known today as Clarence House was the house referred to in the Vestry Minutes, but recent investigations by the Borough Librarian tend to show that despite its name, Clarence House was never occupied by the Duke or by Mrs Jordan and moreover that it was not one of the Sayer properties as had seemed possible.

After 1800

Robert Sayer died – of a lingering illness to quote the Gentleman's Magazine – in January 1784 at Bath and was buried at Richmond in the cemetery in Vineyard Passage. His will reveals that he had property in Birmingham as well as in London and Richmond. Eventually it all devolved upon his son James.

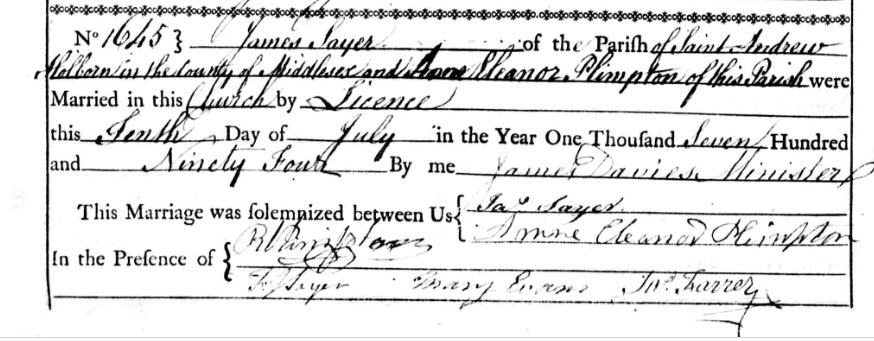

Six months after his father's death James Sayer married Anne Eleanor Plimpton at St James's Clerkenwell.

They were living in Queen Square, Bloomsbury, when, after losing their first child, their son Robert was born on 1st February 1797.

But tragedy was to follow; Mrs Sayer died two weeks later at the age of twenty-eight. A macabre entry in the Family Bible tells us that the baby was "privately christened over his mother's corpse".

The widowed James died in 1803 when he was forty-six. He was then living in Dover Street, Piccadilly, and Robert his seven-year-old son was under the care of the Rev. Mr Goodenough. James's will, in which he is described as of Richmond Hill, nominates his cousin Frances Julia Sayer – still unmarried - as one of the child's guardians. This was a wise choice. A codicil directs that the testators body shall on no account be interred without being "opened" and names three gentlemen, one of whom, it is hoped, may agree to undertake that office.

His son Robert, despite of his inauspicious entry into the world, seems to have had a prosperous life. After going to Eton he was admitted to Lincoln's Inn in 1817 and in 1820 he married Frances the daughter of G.H Errington Esq. of Coton Hall, Staffordshire. The marriage took place at Bagnères-de-Bigore in the south of France, Robert being described as of Trinity College Cambridge when he had just taken his B.A. degree. He became an M.A. three years later. For a short while he and his wife lived in Essex and after 1823 until about 1844 at White Lodge, Sibton, Suffolk. Robert Sayer was High Sheriff of Suffolk in 1835 and later lived for a time at Pierrepont Lodge, Surrey. In 1850 he inherited all the property of his aged cousin and former guardian Frances de Pougens. Her property would have included the Manor House, Marshgate, Richmond, which came to her on the death of her brother Edward and which is given as Robert Sayer's address in a Richmond Directory for 1853. He sold part of the Manor House grounds to the London and South Western Railway but the house itself and its gardens remained in the family's hands until sold by auction in July 1914 for £2,750. The whole area has now been built over but the names Manor Road and Manor Grove mark the site. The house actually stood where Manor Road meets Sheen Road.

The date of Robert's death has not been discovered. "Alumni Cantabrigienses", giving an outline of his school and college career, ends it by stating that he died on 3 August 1826. This manifest error seems to have been due to an announcement in the Gentleman's Magazine of the death on that date of another Robert Sayer at Thurloxton, Somerset.

The elder children of Robert and Frances Sayer were Frances Julia, born in 1824, James Robert Steadman, born in 1826, and Louisa Cardine born in 1828. These were followed by another daughter Emily Ann, and in 1832 a second son Frederick. Emily married Douglas Parry-Crooke of Darsham, Suffolk , and I am indebted to their grandson, Mr Charles Parry-Crooke, for allowing me to study the 1763 pedigree and the elder Robert Sayer's family Bible; also for some very interesting verbal information.

James, the elder of the two sons referred to above, entered the Army, his commission as a Cornet in the King's Dragoon Guards being purchased on 23 May 1845. Subsequent commissions – all by purchase - were as follows : Lieutenant 1848, Captain 1850, Major 1857 and Liet-Colonel 1859. After serving in the Crimea he was posted to India, where at Oostacamund, Madras, his marriage took place in 1862. It is said that in those days James was anything but well-off and perhaps that is why he married the daughter of a wealthy Calcutta merchant. The lady's name was Sarah Ann Blundell and she is reputed to have been cordially detested by the rest of the family. James Sayer was promoted to full Colonel in 1864 and finally became a Leut-General and a K.C.B with honorary Colonelcy of his regiment. He died in London in 1908 leaving one daughter, Ethel Florence who died unmarried. It was after Lady Sayer's death that Miss Sayer sold the Zoffany pictures.

The General's younger brother Frederick was born 2 August 1832. He went to Rugby in 1846 and on 20 November 1850 the Queen signed his Commission as 2nd Lieutenant in the 23rd Regiment of Foot, the Royal Welsh Fusiliers. His portrait in uniform was painted by O.Oakley in February 1851 and was later inherited by his grandson William Sayer in South Africa.

He was appointed 1st Lieutenant on 4 October 1852.

At this time Frederick Sayer was accounted the fastest runner over 100 yards in the British Army and beat Lieutenant John Astley-Slater of the Scots Guards in a memorable race run at Windsor in the presence of the Court. The guardsman was fully expected to win and large sums of money had been wagered on the event. Frederick's athletic prowess, however, was soon cut short, for in September 1854 a wound received at the battle of Alma left him lame for the rest of his life. When Queen Victoria distributed decorations in St James's Park he was wheeled past her in a bath-chair to receive his medal.

Frederick was promoted to Captain at the end of 1854 and in the following August was appointed Deputy Assistant Quartermaster General. He is said to have been a remarkably attractive young man and a great favourite at Court. A letter from Queen Victoria to King Leopold of Belgium gives some indication of this. Writing from Windsor on 29 January 1856 she says :" My dearest Uncle, you will kindly forgive my letter being short but we are going to be present this morning at the wedding of Phipp's daughter with that handsome, lame young officer whom you remember at Osborne. It is quite an event and takes place at St George's Chapel which is very seldom the case…..".

The bride's names were Maria Henrietta Sophia but she was better known as Minnie.

Maria Phipps

She was the eighteen-year-old daughter of Colonel the Hon. Charles Beaumont Phipps, keeper of the Queen's Privy Purse, Treasurer to the Household of Prince Albert and a younger brother of Lord Normanby. As the Queen's letter shows, both she and the Prince attended the ceremony, and the royal wedding present was some fine silverware; a monogrammed dinner service and a tea-set. This splendid heirloom is now in the possession of the Sayer family in South Africa.

Altogether it was no more than fitting that the first of the eight children of Frederick and Minnie Sayer should have been resoundingly christened Victoria Alma. The baptism took place at Windsor in December 1856.

When the Queen invested recipients of the V.C. and reviewed the Crimean troops in June 1857 Captain Sayer D.A.Q.M.G. headed the royal entourage as it processed in to Hyde Park. In August his Majesty Napoleon III nominated M. Frederic Sayer a Chevalier of the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honour, 5th class, in recognition of his distinguished service before the enemy on the late war. The Queen's consent to the acceptance of the insignia by Captain Sayer, late of the 23rd Regiment is dated 17 December 1857. That year also saw the publication of his collection of despatches and other military records relating to the Crimean war.

The good fortune so far enjoyed by Frederick Sayer was evidently resented in some quarters, for in January 1858 the Times printed a letter protesting against the bestowal of so many favours and honours on Captain Sayer. This drew a spirited reply on 28 January from Sir D.A.C Montagnes Darling late of the Light Division, to the effect that Captain Sayer had joined the Light Division Transport while in Bulgaria before the Crimea was invaded; that he fell ill during the voyage across the Black Sea but, declining to remain on board with the other invalids, followed the Division independently after it landed; and that though he might well have remained with the rearguard, he obtained leave to rejoin his corps as soon as the fighting at Alma began. Here, nine out of fifteen officers of the 23rd Foot were killed and one of Captain Sayer's ankles was destroyed by a musket shot. He was taken to Scutari and after some months sent back to England – a cripple for life.

A rejoinder to this letter, signed by "A.Linesman" was written on the following day. It was admitted that Captain Sayer had volunteered for duty, though unwell, and that no reflection could be cast upon his gallantry or courage but it was pointed out that owing to his wound he saw scarcely any war service and yet had been "overwhelmed with decorations, staff appointments and Court favour to an amount that can only be accounted for by his subsequent matrimonial connection with Privy Purse". Captain Sayer, so the letter continued, was allowed – contrary to all precedent – to retire on his half-pay when the 23rd was about to sail for China and since then had filled three distinct staff appointments. Moreover, far from being a hopeless cripple entirely incapable of regimental duty, he presented at Court balls and festivities "a perfect model of youth, health, manly beauty and vigour". Are we, asks "Linesman", to believe, as intimated by the Royal Gazette, that Captain Sayer had been selected out of all the British Army for singular decoration by the Emperor of the French? And if so, for what? – because he served with the Commissariat, because he was for a few days in the Crimea and was wounded in the foot? – because he avoided hard and dangerous duty in the Crimea, China and India? – or because he married a Phipps?

No doubt much to "Linesman's" annoyance, Frederick Sayer was appointed Police magistrate at Gibralter in 1859, but six years later, in December 1865, he was obliged to resign from his post owing to bad health. Two events during those six years may be noted: in 1862 his "History of Gibraltar" was published and in January 1863 he was elected to a fellowship of the Royal Geographical Society.

It may be inferred that despite "Linesman's" ill-natured comments, Frederick Sayer was a very able and industrious servant of the Crown, for in 1867, when, still under forty, he was appointed to the Governor Generalship of New South Wales. But tragically enough he died at Cairo in February 1868 while on his way to take up his duties in Australia. A letter from Princess Louise has been preserved in which she condoles with Harriet Phipps on the death of her brother-in-law and refers to "poor dear Minnie". Harriet Phipps was a lady in Waiting until the death of Queen Victoria.

On 4 December 1872 Minnie Sayer married Captain William Chaine of the 10th Hussars. Later, as Lt. Col. Chaine M.V.O. he was Master of Ceremonies to Queen Victoria and then to King Edward VII.

William Chaine

An indenture dated 1874 appointing Chaine a trustee of his wife's final marriage Settlement notes that all eight children of Frederick and Minnie Sayer were still living.

Colonel and Mrs Chaine, with apartments in Kensington Palace, remained in close touch with the Court, Minnie being a personal friend of princess (later Queen) Alexandria. A Card written on 21 June 1893 by the future King George V is among the Sayer papers. It is signed "George" and thanks Mrs Chaine for her charming wedding present. There is also a telegram offering Colonel and W. Chaine and Mrs Harriet Phipps admission to the Throne Room at Buckingham palace when the body of King Edward VII lay in state there in May 1910. The Chaines died at Kensington palace within a year of each other; she on 21 December 1915 and he the following July.

As indicated above, Frederick and Minnie Sayer had seven children after the birth of Victoria Alma in 1856. They made their appearance for the most part at yearly intervals as may be seen from the details entered in their Old Prayer book. Our knowledge of their later lives is in most cases scanty. Victoria Alma died a spinster but all her three sisters married. Evelyn, who died childless before 1910, had married a Mr Slade – against the wishes of Mrs Chaine. The result was that mother and daughter are said to have become totally estranged. Mabel Sayer became Mrs Verschoyle and neither she nor the youngest sister Harriet, whose married name was Hay, left any children.

The eldest son, Frederick, was born in 1859. He served for a few months as a constable in the North West Mounted Police in Canada, purchasing his discharge in December 1885. His conduct was noted as "very good". He is next heard of in October 1889 when the Bus proprietors of Sydney, Australia presented him with a testimonial before his departure to England. No other particulars of his life, or the date of his death, have been found.